For the first couple of years of the coronavirus pandemic, the crisis was marked by a succession of variants that pummeled us one at a time. The original virus rapidly gave way to D614G, before ceding the stage to Alpha, Delta, Omicron, and then Omicron’s many offshoots. But as our next COVID winter looms, it seems that SARS-CoV-2 may be swapping its lead-antagonist approach for an ensemble cast: Several subvariants are now vying for top billing.

In the United States, BA.5—dominant since the end of spring—is slowly yielding to a slew of its siblings, among them BA.4.6, BF.7, BQ.1, and BQ.1.1; another subvariant, XBB, threatens to steal the spotlight from overseas. Whether all of these will divvy up infections in the next few months, or whether they’ll be pushed aside by something new, is still anyone’s guess. Either way, the forecast looks a little grim. None of the new variants will completely circumvent the full set of immune defenses that human bodies, schooled by vaccines or past infections, can launch. Yet all of them seem pretty good at dodging a hefty subset of our existing antibodies.

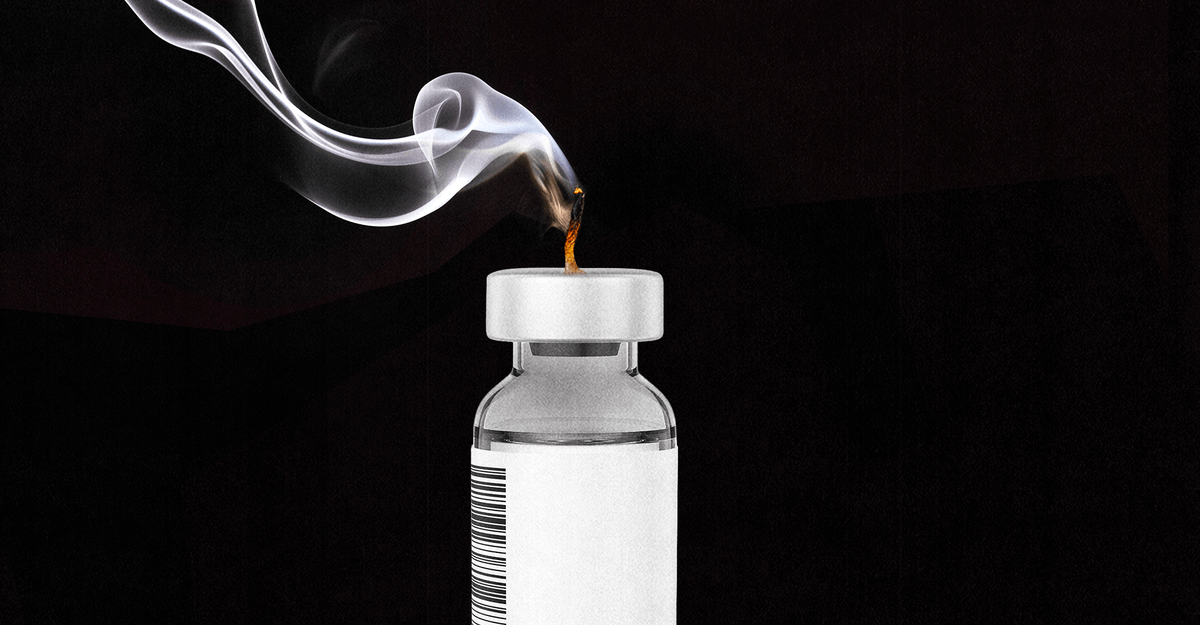

For anyone who gets infected, such evasions could make the difference between asymptomatic and feeling pretty terrible. And for the subset of people who become sick enough to need clinical care, the consequences could get even worse. Some of our best COVID treatments are made from single antibodies tailored to the virus, which may simply cease to work as SARS-CoV-2 switches up its form. Past variants have already knocked out several such concoctions—among them, REGEN-COV, sotrovimab, and bamlanivimab/etesevimab—from the U.S. arsenal. The only two left are bebtelovimab, a treatment for people who have already been infected, and Evusheld, a crucial supplement to vaccination for those who are moderately or severely immunocompromised; both are still deployed in hospitals countrywide. But should another swarm of variants take over, these two lone antibody therapies…