On February 26, missiles rained down on Kyiv as the Russian army tried to enter the city. During a lull in the fighting, Tamara Hundorova, one of Ukraine’s foremost literary critics, sat calmly in front of her laptop and delivered an online lecture on the Ukrainian modernist writer Lesya Ukrainka, a canonical fin de siècle poet and playwright.

Ukrainka is often reduced to her youthful patriotic verses, which every schoolchild in Ukraine reads. Hundorova, however, spoke of her as a complex dramatist, a feminist, and an anti-colonial thinker. As she ended her talk, she sighed and said:

I never thought I’d be speaking to you from Kyiv on the front line, that I’d be sleeping on the floor in the corridor in fear of bombs, waking up to the sounds of explosions, watching children play in bomb shelters instead of on the playground. But I’m amazed by the courage of Ukrainians, all trying to help our defenders with such belief and such love. You know, this war of Putin’s has made Ukrainians into real Ukrainians.

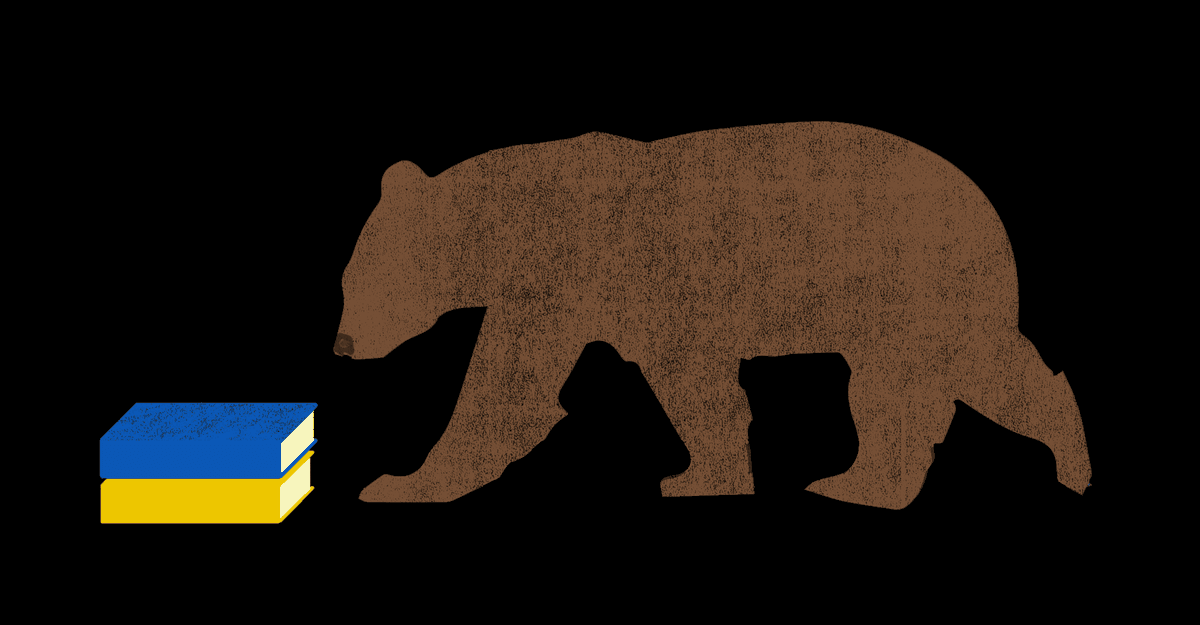

Ukrainians frequently speak of the need to become Ukrainians: to consolidate their culture, language, and institutions after centuries of imperial domination. What Ukrainians see as a work in progress, however, Russia interprets as weakness; it views Ukraine as an accident of history. Indeed, before he ordered in the tanks, Vladimir Putin spent nearly an hour on television trying to convince Russians that Ukraine was nothing but an “anti-Russia” engineered by the West on “our historical land.”

Ukrainian national identity is not an accident, nor was it invented by the West. But for centuries, Ukrainians have struggled to fend off attempts to erase their culture. In the early 19th century, Russian publishers accepted Ukrainian literature only if it was ethnographic, comedic, or apolitical. (Serious literature had to be in Russian.) Successive laws in 1863 and 1876 led to the effective banning of…