During clinical training, novice learners adapt to navigating the complex working environment while developing their knowledge, skills, and attitude. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in the United States provides the guidelines for varying levels of supervision a resident physician receives from the attending physician, starting from direct supervision and transitioning gradually to indirect supervision [1]. With an appropriate level of supervision, trainees provide high-quality patient care, progressively earning autonomy and trust of faculty before graduating to become independent practicing physicians [1].

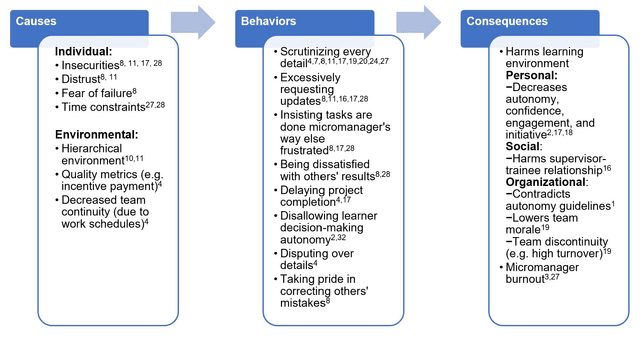

The appropriate level of supervision a learner should receive is up to the subjective interpretation of the learner and/or supervisor in clinical care. When surveying residents and attendings, residents tend to prefer less supervision than the amount their supervising attending physician wishes to give [2,3]. If the supervision reaches an excessive level, attendings can be known amongst the residents as “micromanagers” [4]. Micromanagement is defined as a supervisory style of “hovering” and directly commanding all of the details, rather than giving space to the trainee assigned to the task [5]. In the context of attending-resident supervision, micromanaging attendings tend to scrutinize the decisions already made appropriately by the trainees. Some examples of micromanaging behaviors may include things such as delaying patient discharge, disputing over medications, and requesting unnecessary consultations (Table 1) [4]. This increased supervision/scrutiny has been shown not to have any reduction in medical errors and instead interferes with resident education [6]. As a result, micromanagement has been perceived by residents to impede their autonomy in the clinical decision making process thereby affecting their learning and professional development [7]. This article was previously presented as an oral presentation at…