Jean Jacques Dessalines is now being re-evaluated in the West, recognized as a head of state, strategist, and abolitionist, rather than solely as a man of war. This new perspective challenges decades of reductive narratives that have overshadowed his broader achievements.

A new book by historian Julia Gaffield reveals a different side of Emperor Jacques I.

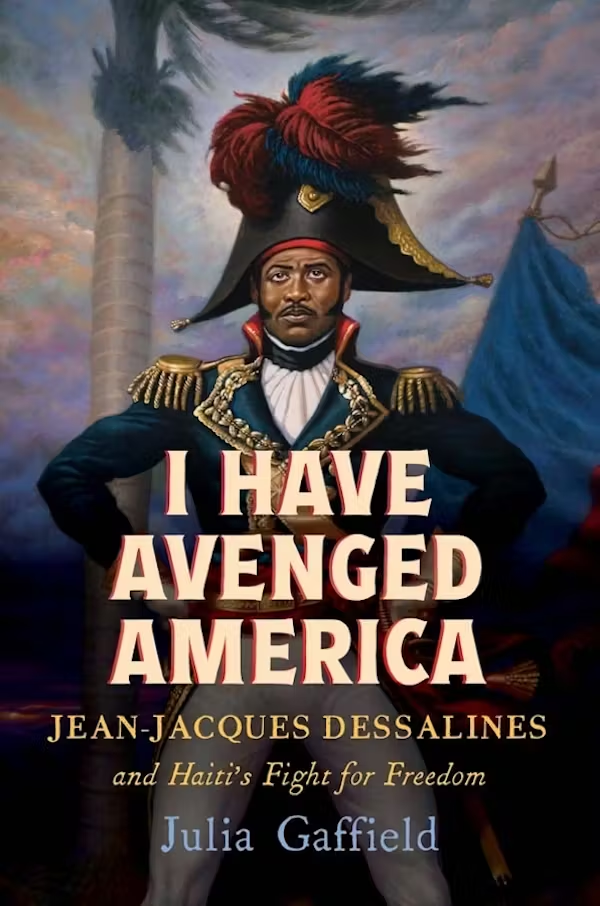

In her book “I Have Avenged America: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti’s Fight for Freedom” introduces her portrayal of Dessalines. In it, Gaffield presents Dessalines not just as a warrior, but as a diplomatic, state-building founder.

In an interview with The Conversation, Professor Gaffield sought to introduce U.S. readers to the full scope of Dessalines’s achievements.

Every Oct. 17, Haiti commemorates the 1806 assassination of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the country’s first head of state after independence.

Celebrated at home for ending slavery and toppling French colonial rule, he is frequently vilified abroad, his memory reduced to the violence of revolutionary warfare and the 1804 killings. That reductive view, historian Julia Gaffield argues, is challenged by a biography grounded in extensive archival work. In her words, “the Dessalines that emerged in my research didn’t match the Dessalines that was being presented in public,” she told The Conversation, noting that in dominant narratives Dessalines is alternately heroized and demonized.

“He just doesn’t get the same attention that Toussaint Louverture gets,” Gaffield observes, seeing in that imbalance part of a long international process of delegitimization.

This legacy is shaped by a double standard: Dessalines is labeled as “savage” by some and solely as a forceful leader by others, reflecting a racist bias that simplifies his role. Gaffield emphasizes that he was far more than a military leader; his efforts at state-building, diplomacy, and abolitionism are central to understanding his impact. The argument throughout is that Dessalines deserves recognition for this multilayered legacy.

A double standard on colonial violence and Haitian resistance

The Conversation investigates why Dessalines is so frequently singled out.

Gaffield explains that French chroniclers held him and other Haitian revolutionaries to double standards, minimizing colonial atrocities while accusing Haitians of violating the rules of war. Once Dessalines emerged as an antagonist, this bias strengthened, aiming to undermine the legitimacy of Haitian independence within the global arena. This context is crucial to understanding why Dessalines’s legacy has been so contested.

After Jan. 1, 1804, Dessalines ordered some French colonists executed. This was justified then as protection against future invasions, which the French often threatened, and as vengeance for slavery’s crimes, including Bonaparte’s 1802 expedition. Gaffield stresses, “not every white person was killed.” British and American merchants were safe. Poles in Haiti were welcomed, and some French were granted citizenship. Reported figures vary. Still, hostile commentators called it a “massacre,” a narrative “destined to demonize Haitians and ensure that independence failed.” Gaffield adds that focusing only on Dessalines’s violence ignores colonial violence, which shaped Haiti far more than “anything Dessalines did or didn’t do.”

Dessalines’s legacy experienced “ebbs and flows” in 19th-century Haiti, in a context where the country’s sovereignty was not recognized — the United States did not recognize Haiti until 1862, Professor Gaffield notes.

In 1904, at the centennial of independence, his place was secured in the national pantheon: the anthem composed for the occasion, “La Dessalinienne,” bears his name.

Today, as Gaffield points out, he has come to embody sovereignty and reject outside interference. However, a more nuanced view of him has begun to emerge outside Haiti only recently—and not without resistance.

Gaffield says researching Dessalines means facing a biased documentary landscape. “None of the images we have of Dessalines were done by anyone who ever saw him,” she explains. She remembers an outrageous engraving—Dessalines shown with the severed head of a white woman—published in Louis Dubroca’s 1804 biography and a Spanish translation. This racist iconography framed him as “born in Africa” and “savage.”

For her book cover, the historian chose a painting by Haitian artist Ulrick Jean-Pierre: Dessalines “standing boldly and confidently,” feathers and trees swaying — a leader upright in a “stormy, unsettled and complicated era.”

As for the archives, “Most of the records on the Haitian revolution were written by people who opposed the revolutionaries.” However, “there is nothing from the other side”: Haitian texts, as well as Dessalines’s own letters and declarations, exist and “haven’t been taken as seriously as they could have.” Confronted with the recurring refrain — “There’s not a lot of sources for that” — Gaffield adopted an eclectic strategy, consulting archives from the United States, France, the Netherlands, England, the Vatican, Jamaica—anywhere the Haitian Revolution left a trace.

Over the course of the inquiry, Gaffield says she gained a clearer sense of the personal dimension of Dessalines’s trajectory, beyond the narrow lens of diplomacy and statecraft.

Through extended family, colleagues, and the risks he took, a throughline emerges: “At the cost of personal relations and personal safety, he fought for freedom – and that was the driving force behind everything for Dessalines: the fight to abolish slavery.”

https://ctninfo.com/?p=37634&preview=true

Credits and references:

Work cited: I Have Avenged America: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti’s Fight for Freedom, Julia Gaffield.

Iconography referenced: engraving linked to Louis Dubroca’s 1804 biography; painting by Ulrick Jean-Pierre selected for the cover.

By the newsroom — Based on a The Conversation piece (Oct. 15, 2025), interview with historian Julia Gaffield, Associate Professor at William & Mary, about her book I Have Avenged America: Jean-Jacques Dessalines and Haiti’s Fight for Freedom.