US authorities are using air passenger data to locate immigrants.

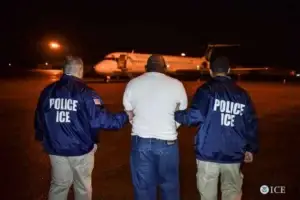

The Trump administration has implemented a surveillance system that allows for the detention and deportation of undocumented immigrants on domestic US flights. As reported by the New York Times, this initiative raises important questions about the boundaries between aviation security and immigration law enforcement.

Since last March, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) has sent complete passenger lists from US airports to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) several times a week. ICE cross-references this information with its database to identify individuals with deportation orders and dispatches agents to make arrests, according to the New York Times.

This cooperation between federal agencies represents a significant policy change.

According to a former TSA official cited by the Times, the aviation security agency “did not previously get involved in criminal or immigration matters domestically.” Airlines have long provided passenger information to TSA after a reservation is made, but this data was used solely for national security checks, particularly against terrorist watchlists.

The exact number of arrests resulting from this program is unclear. However, a former ICE official told the newspaper that in their region, 75% of system alerts led to apprehensions.

The Case of Any Lucía López

The program became public following the arrest of Any Lucía López Belloza, a 19-year-old Honduran student, on November 20 at Boston’s Logan Airport. She was arrested before boarding a flight to Texas to join her family for Thanksgiving and deported to Honduras two days later.

Internal documents obtained by the Times indicate that her flight information came from the Pacific Enforcement Response Center, an ICE office in California that is central to the program. This center sends dozens of tips daily to immigration agents nationwide, including flight numbers, departure times, and sometimes photos of targets, often just hours before takeoff.

The document explains that this is a “collaboration with the Transportation Security Administration to send actionable leads to the field regarding aliens with a final order of removal that appear to have an impending flight scheduled,” the New York Times reported.

López had no criminal record. As a freshman business student at Babson College, she was unaware that a deportation order had been issued against her in 2018, when she was a minor. She told the Times that her boarding pass did not work, and an agent directed her to customer service. “That’s where they were waiting for me,” she explained.

“‘Oh, you’re Any,'” one of the federal agents told her, according to her testimony. She recalled insisting on catching her flight, but the agent responded: “I don’t think you’ll even be on that plane.”

A Strategy Adopted by the Trump Administration

The Department of Homeland Security, which oversees both ICE and TSA, defends this approach unequivocally. “The message to those in the country illegally is clear: the only reason you should be flying is to self-deport,” said Tricia McLaughlin, a department spokesperson.

This initiative is part of a broader strategy to increase arrests and deportations. Earlier this year, Stephen Miller, a senior White House advisor, set a goal of 3,000 immigrant arrests per day and met with senior ICE officials to discuss methods to increase deportations.

Scott Mechkowski, former deputy director of ICE’s New York office, praised the program in comments reported by the Times: “The administration has turned routine travel into a force multiplier for removals, potentially identifying thousands who thought they could evade the law simply by boarding a plane.”

Immigrant advocacy organizations strongly criticize what they consider a campaign of intimidation. “This is another attempt to terrorize and punish communities and will make people terrified to ever leave their homes for fear of being unjustly detained and disappeared out of the country before they have a chance to contest the detention,” said Robyn Barnard, senior director of refugee advocacy at Human Rights First.

Claire Trickler-McNulty, a former ICE official under the Biden administration, raised practical concerns in the Times: “If you have more officers conducting arrests at airports, it puts more strain on the system, delays and complications may annoy and frighten some travelers, and those who are unsure about their status will move away from air travel.”

Beyond Airports: Expanded Use of Federal Data

The airport program is one part of a broader effort. The Trump administration is seeking to use all federal databases to locate immigrants. Earlier this year, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) agreed to provide migrant addresses to ICE, but a federal court blocked this collaboration in November.

The case of Marta Brizeyda Renderos Leiva, a Salvadoran woman arrested in late October at Salt Lake City Airport, also demonstrates the system’s effectiveness. Internal documents show that her flight information was sent to local agents by the same California office. A video of her arrest shows her screaming as agents removed her from the airport.

Now in Honduras, Any Lucía López is seeking ways to continue her university studies. She told the Times she misses going to church with her family, shopping at Texas supermarkets, and eating her mother’s cooking. Her Thanksgiving trip resulted in permanent deportation, highlighting an immigration policy that no longer distinguishes between daily life and law enforcement.